Kingmakers

Cast of Characters: Who Reshaped the Near East, and Beyond

1. The Proconsul

Evelyn Baring, Lord Cromer (1841-1917)

He was Egypt’s shadow pharaoh, with a deceptive title (British Consul) and unbounded authority, who brought a banker’s icy discipline and fiscal thrift to an insolvent country, anticipating the policies of the World Bank and IMF. Yet after his reign of twenty-four years, Egypt remained mostly poor, and mysteriously (to Britons) ungrateful. Baring financed the building of the first Aswan Dam, the precursor of the many giant projects to come (including the second Aswan Dam). He is remembered, too, as the offstage eminence who failed to save General Gordon at Khartoum. In an epic sequel, Baring avenged his death and turned the rebellious, Islamist Sudan into an Anglo-Egyptian vassal.

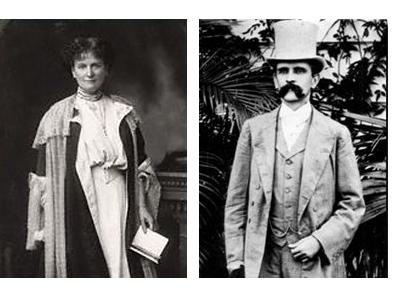

2: The Empire's Power Couple

Dame Flora Shaw, Lady Lugard (1852-1929) and

Frederick Lord Lugard of Abinger (1858-1945)

She was the first Victorian gentlewomen to rise from the middle ranks of British journalism to its Alpine peak, The Times of London. In Egypt during the winter of 1888-9 as a correspondent for both the Pall Mall Gazette and The Manchester Guardian, she was briefed by Evelyn Baring, and fell under the spell of his New Imperialism, whose cause she then espoused as The Times’s peripatetic Colonial Editor. From 1893 to 1900, in five-hundred articles for what was the Empire’s quasi-official house-organ, she coined the name Nigeria, and approved the expansionary schemes of Cecil Rhodes, becoming a co-conspirator in the 1897 Jameson Raid, the failed plot to bring down the Boer regime in gold-rich Transvaal. In 1902, she made a suitable match with Sir Frederick (later Baron) Lugard, the proconsul who established the giant federation (which she named) Nigeria; it was Lugard who codified the precepts of Indirect Rule (his capital letters) which the British sedulously applied to the Middle East while Lady Lugard became his trumpet, as well as that of the Britannic Empire.

3: "Dr. Weizmann, It's a Boy"

Sir Mark Sykes (1879-1919)

First in a procession of eminent diplomatic Arabists, Sykes studied Near Eastern languages at Cambridge University under the formidable Orientalist E.G. Browne, and even as a student foraged extensively in Ottoman provinces. Before his premature death at forty (from influenza), he and M. Picot in 1916 drew the lines in the sand that covertly divided Arab lands between Britain and France. More surprisingly, as an adviser to the Foreign Office, he became an ardent promoter of Zionism, preparing the way for the Balfour Declaration that designated Palestine as a national home for the world’s Jews; in a real sense, he was Israel’s godparent. As the DNB remarks of him, he was also blessed with “a turn of humour, a pleasing voice, and an unusual measure of youthful audacity.”

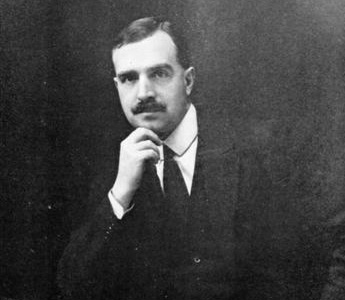

4: The Acolyte

Sir Arnold Wilson (1884-1940)

Now all but forgotten, Colonel A.T. Wilson as Acting Civil Commissioner of Mesopotamia during and after World War I was the territorial architect of today’s Iraq. As a young Indian Army officer in 1908, he was present at the first discovery (in southern Persia) of oil in the Near East; later, he saw to it that oil-favored Mosul was incorporated with Basra and Baghdad to form the new Iraqi state. An acolyte of Empire whose gods were Curzon and Kipling, Wilson sought vainly to turn Iraq into a formal British protectorate rather than a nominally sovereign state. When World War II broke out, he enlisted in Bomber Command as a rear gunner, and died at fifty-five when his Lancaster plunged in flames over Dunkirk (as dramatized in the classic British film, One of Our Aircraft Is Missing).

5: "Dreadfully Occupied in Making Kings and Governments"

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926)

Born to an affluent industrial dynasty in England’s County Durham, young Gertrude dazzled with her range of knowledge, her air of certitude, and her daring. She was the first woman to qualify for a coveted First Class degree in modern history at Oxford. During a subsequent Grand Tour, she scoured the Ottoman Near East, mastering its ways and languages. As a pioneering field archaeologist, she learned to live like, and with, the Bedouin. Recruited by British intelligence during the First World War, she helped ignite the Arab Revolt against the Turks, and then worked with T.E. Lawrence to enthrone the Hashemite Faisal I in Iraq. Disheartened by an ingrate monarch, her counsel no longer sought by her superiors, Bell died of an overdose of sleeping pills, just short of her fifty-eighth birthday.

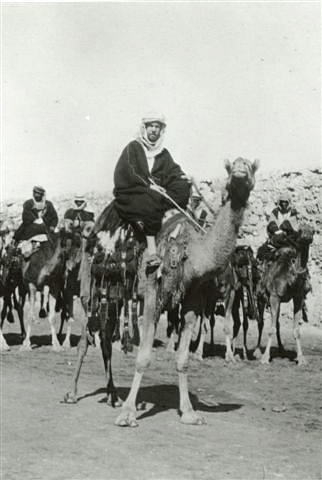

6: The Frenzy of Renown

Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888-1935)

Known to the world as Lawrence of Arabia, he recalls Oscar Wilde’s assertion that he put his talent into his work, his genius into his life. “He loved fantasy,” E.M. Forster wrote of Lawrence, “and leg-pulling and covering up his tracks, and threw a great deal of verbal dust, which bewilders the earnest researcher.” Variously depicted as cinematic hero, imperialist conjuror, colossal humbug, neurotic self-hater and anti-war idealist, Lawrence was withal a kingmaker, and proud of it. As a British agent in World War I, he brought gold, weapons and media celebrity to the Arab Revolt led by Hussein, Sherif of Mecca, then stage-managed the crowning of two Hashemites, in Iraq and Jordan (with the crucial help of Winston Churchill). His deeds made his name, but his prose ensured his immortality; like Wilde, he was first and foremost an artist.

7: The Apostate

Harry St. John Philby (1885-1960)

Hell hath no fury greater than a first-rate civil servant scorned. “Jack” Philby had every reason to expect a full and satisfying imperial career culminating in a knighthood. He excelled at Oriental languages, initially at Cambridge where he studied with the renowned E. G. Browne, then as a district officer in the elite Indian Civil Service, capped by his feats during World War I as an intrepid explorer of Arabia’s empty quarter. Yet feeling repeatedly passed over by his inferiors, Philby acquired a canker of resentment that metastasized in Baghdad. The break came in 1920, when the candidate Philby had favored to lead newborn Iraq, Sayyid Talib, son of the Naqib of Basra, was peremptorily snatched by British soldiers and exiled to Ceylon to ensure the accession of Faisal. A furious Philby resigned, and transferred his loyalty to the Hashemites’ arch-rival, Ibn Saud. Jack’s revenge was complete in 1933, when as middleman he secured for an American oil company the exclusive concession to Saudi oil – the greatest transfer of resources in the 20th century, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. In a sardonic finale worthy of John le Carré, Philby’s son Kim – nicknamed after the Kipling boy-spy --turned out to be Britain’s most notorious Soviet mole.

8: "A Splendid Little Army"

Sir John Bagot Glubb, called Glubb Pasha (1897-1986)

Glubb Pasha’s name has a familiar ring but even students of history commonly have trouble remembering who he was. He was in truth a key figure during Britain’s fifty-year moment in the Near East, a seasoned officer who led Jordan’s Arab Legion and stoutly upheld the Hashemite claims of Abdullah I. As a Royal Engineer serving in France during the Great War, he was thrice wounded, once almost mortally in the jaw. In 1920, Glubb was posted to Iraq where he became a devotee of Arab culture, history and language, earning the nickname “Father of the Little Jaw.” Credited with being the first to turn anarchic Bedouins into disciplined soldiers, he showed what his recruits could do in Iraq by curbing murderous raids by Ibn Saud’s Wahabis. In 1939, he was named commander of Jordan’s Arab Legion, which shortly thereafter intervened in Iraq to suppress a pro-Nazi coup, and which swiftly occupied the West Bank and East Jerusalem during Israel’s 1948 War of Independence. But with the rise of Nasserism and Baathism, Glubb Pasha became an embarrassment to the new young king Hussein, who in 1956 dismissed him, giving him twenty-fours to depart. It was this event that precipitated the Suez Crisis, the debacle that endded Britain’s moment of paramountcy in the Middle East.

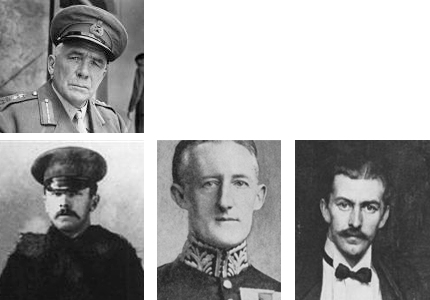

9. A Very British Coup

General Edmund Ironside, 1st Baron Ironside (1880-1959)

Sir Percy Sykes (1867–1945)

Sir Percy Cox 1864–1937)

Sir Percy Loraine (1880–1961)

Three Percys – Sykes, Cox and Lorraine – were instrumental in empowering Reza Khan Pahlavi, who ascended Iran’s Peacock Throne in 1926. Their partner and precursor was Edmund Ironside, a Zelig of the late British Empire. Standing six-foot-four (and inevitably nicknamed “Tiny”), Major-General Ironside, like the ubiquitous Woody Allen character, played a front-bench role in all of his kingdom’s 20th century wars, declared or otherwise. An artillery officer who qualified as an army interpreter in seven languages, he used his fluency in Afrikaans to pose as a Boer driver covertly accompanying a German expedition to South-West Africa. But his claim to our attention rests on his role in establishing the Pahlavi dynasty while commanding anti-Bolshevik British forces in north Persia. There he spotted another six-footer, Reza Khan, an officer in the Cossack Brigade. “I had seen only one man who was capable of leading the nation,” he recalled. “He was Reza Shah, the man who would be in charge of the only efficient armed force in the country.” In due course, the upstart Pahlavis seized the decrepit Peacock Throne, and Ironside moved on, working with Churchill to oppose appeasement of Hitler (whom he met and toasted to “Brotherhood with England,” adding tipsily in 1937, “but only for two years.”). After serving briefly during the Battle of Britain as commander-in-chief of the just-born Home Guard, he faded with silent dignity to his farm in Norfolk.

10. The Quiet American

Kermit (Kim) Roosevelt (1916-2000)

Restored to power in 1953 by a CIA-orchestrated coup, the Shah of Iran said to Kim Roosevelt, “I owe my throne to God, my people, my army – and to you!” Roosevelt (a grandson of TR) went on to relate that by “you,” Iran’s ruler really meant “me and the two countries – Great Britain and the United States – I was representing. We were all heroes.” Time has qualified that judgment, but there’s no doubt that the covert plan to save the Shah marked the critical passing of the kingmaking scepter from London to Washington. Britain alone could not depose Prime Minister Mossadegh after he infuriatingly nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in 1951, and initially President Truman and Secretary of State Acheson were sympathetic to Mossadegh. That changed when the Republicans under Eisenhower assumed office in 1953. The British produced a plan aimed at thwarting alleged Soviet designs on Iran, and their alarmed American cousins eagerly signed on. When the Shah failed in his attempt to dismiss the popular Mossadegh, and fled the country, Cairo station chief Kim Roosevelt provided the cash that filled the streets with screaming pro-monarchist mobs. Thus were sown the seeds that bore the bitter fruit of the 1979 Islamic revolution against the Great and formerly Great Satans, the US and UK, and their nest of spies.

11. The Apprentice Sorcerer

Miles Copeland (1917-1991)

A spy for all seasons, Miles Copeland stood out even among the very bright Ivy Leaguers who, post-1947, dominated the founding generation of the Central Intelligence Agency. Like most of his cohort, he came to the agency following wartime service in the OSS or military intelligence. Unlike most of the CIA’s “very best men,” he was brashly indiscreet, an Alabama native and former jazz trumpeter who once played in Glenn Miller’s band. He reveled in unconventional covert tricks, such as fixing the astrological forecasts of credulous third-world leaders. For two decades, the Near East was his turf. Between rigging elections in Syria he assisted the rise of Gamal Nasser, to whom he offered a blatant “personal gift” of $3 million dollars, in cold cash. Affronted, the scornful Egyptian responded by using the money to build the Cairo Tower, the city’s highest structure, taller than the largest pyramid, thereafter nicknamed by the knowing as “Roosevelt’s Erection” (referring to Kim). All this Copeland related in a sequence of revealing books, beginning with The Game of Nations (1979), written in Britain, where he lived until his death, and where one of the authors dined memorably with him near his riverside home.

12. The Man Who Knew Too Much

Paul Wolfowitz (1943 - )

With Paul Wolfowitz, Deputy Secretary of Defense in G.W. Bush’s two administrations, a century of history has come full circle. His influence on American policy recalls that exercised by the redoubtable Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914), the radical-minded Colonial Secretary who brimmed with optimism and believed it was Britain’s duty to use every means to protect and expand the Empire’s civilizing mission. Operating from nominally second-level positions, both civilians gave intellectual weight to the case for waging wars of choice for political and strategic reasons, acting alone if need be. With his calm voice and professorial manner, Wolfowitz began pressing for the removal of Saddam Hussein during the First Gulf War, and thereafter led the pack. Immediately after 9/11/01, in a manner described by the pro-Bush Economist as “clever, quick and jumping for the throat,” he brought up Iraq on every occasion. “Hawk doesn’t do him justice,” remarked a onetime colleague. “What about velociraptor?” In the event, as with Joseph Chamberlain in the Boer War, Wolfowitz underestimated the guerrilla skills of a resisting adversary. Six months before the attack on Iraq, in an interview with The New York Times’s Bill Keller, he remarked, “I think getting in is the dangerous part,” to which Keller added “He worries considerably less about the day after.” It proved a misjudgment “Imperial Joe” would have understood.